Update of Protecting and Restoring Flows in Our Southeastern Rivers Report Shows Progress and Need for Continued Improvement

Rivers here in the southeast are special places, ranging from quiet, blackwater rivers in the Coastal Plain to raging whitewater in the mountains and everything in between. Over the last three years, since my colleague Katherine Baer and I, with the support of many people, researched and wrote the first edition of the Protecting and Restoring Flows in Our Southeastern Rivers – A Synthesis of State Policies for Water Security and Sustainability report, much has changed. However, the threats and challenges facing the rivers and people who depend on them in this region remain:

Rivers here in the southeast are special places, ranging from quiet, blackwater rivers in the Coastal Plain to raging whitewater in the mountains and everything in between. Over the last three years, since my colleague Katherine Baer and I, with the support of many people, researched and wrote the first edition of the Protecting and Restoring Flows in Our Southeastern Rivers – A Synthesis of State Policies for Water Security and Sustainability report, much has changed. However, the threats and challenges facing the rivers and people who depend on them in this region remain:

- Agricultural water use continues to increase, largely unregulated, increasing water stress in some places;

- Southern cities continue to grow and sprawl, increasing demand for highly treated water; and

- Communities and rivers are tested by climate change, severe drought, and increasing frequency of storms and hurricanes like Florence and Michael.

Since that time, we have also worked with organizations across the southeast to form the Southeast River Flows Peer Learning Network to bring community-based river and conservation groups together to learn from each other, create new alliances, spark innovative and collaborative approaches, and work together to break through the barriers encountered in protecting river flows. One project that has emerged from this collaboration is a communications research project to support river flow protection efforts – join the Making a Splash When Communicating About River Flows webinar on July 24, 2019, to learn all about it.

Over these last three years, it’s been (mostly) encouraging to watch water policy in the southeast continue to evolve – with a few setbacks too. Because so much was changing, we knew it was time to update the report to include what was new. With extensive review, edits and feedback from Curt Chaffin, Alabama Rivers Alliance; John Tynan, Conservation Voters of South Carolina; Jim Redwine, Harpeth Conservancy; Grady McCallie, North Carolina Conservation Network; April Lipscomb, Southern Environmental Law Center, and Peter Raabe with American Rivers, we have updated the report and are pleased to share the new second edition of the Protecting and Restoring Flows in Our Southeastern Rivers – A Synthesis of State Policies for Water Security and Sustainability report.

Some notable highlights of changes over the last three years include:

On the positive side:

- Water Planning

- Alabama – In January, 2018, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey directed state agencies to develop a “roadmap” leading to a water plan for the state. In November 2018, the Alabama Water Resources Management Plan Roadmap was approved and recommended development of an Alabama Water Resources Management Plan by July 2020. The roadmap included definitive budget requests and timelines and identified many important water management issues ripe for additional study, such as instream flows, interbasin transfers, and water monitoring. However, the roadmap only recommends the water plan be a compilation of existing laws and policies, which falls far short of what should be included in a state water management plan.

- South Carolina –In 2018, a State Water Planning Process Advisory Committee (PPAC) was convened to develop a multi-faceted framework for statewide water planning. The framework is expected to guide a stakeholder driven water resource plan, including a defined implementation process, in each of the state’s eight river basins, with a goal of “providing water for human needs while ecologically protecting the resource.” In August of 2018, the state began a process to develop methods for projecting water demands, which will inform the state water plan.

- Tennessee – In late 2018, Tennessee released its “TN H2O” plan. The plan calls for “a comprehensive water resources planning process and planning cycle based on good science and information that includes all major users and stakeholders.” The plan also calls for an assessment of current water resources and recommendations to “ensure that Tennessee has abundant water resources to support future population and economic growth through 2040.” The plan recommends that the state “[d]evelop water budgets for Tennessee’s major basins to forecast water needs and availability with reasonable scientific accuracy.” As the process is in its infancy, the Plan includes recommendations to identify basin-specific needs, priorities, and performance measures, but it remains to be seen how this will play out.

- Georgia – In 2017, the state’s Regional Water Plans were updated to reflect more recent conditions.

- Stormwater management in Georgia – Georgia updated their stormwater regulations to require more on-site retention of stormwater, which means more water will be captured, reused and infiltrated on-site, leading to more recharging of rivers and aquifers and less flooding and polluting of downstream waterways. By December 2020, Georgia’s Phase II stormwater permits will require that the first 1-inch of rainfall be retained on site, to the maximum extent practicable. Phase I requirements were also recently finalized, and are expected to be aligned with the requirements of the Phase II permits. For Georgia’s 11-county coastal management program service area, stormwater runoff has to be retained onsite or adequately treated prior to discharge and, at a minimum, “appropriate green infrastructure practices must be used to reduce the stormwater runoff volume generated by the 0.6 inch rainfall event (and the first 0.6 inches of larger rainfall events).”

- Water Data Collection and Generation – throughout the region, there were advances in efforts to collect and share better water data for management purposes. In North Carolina, for instance, the state completed one additional basin-wide hydrologic model aimed at evaluating water withdrawals and interbasin transfers (this is the fifth of 17 river basins completed, with two others under development). In Alabama, the Assessment of Groundwater Resources in Alabama, 2010-16 report was published and provides new data on groundwater use in the state. In 2017, Georgia revised their program for measuring farm uses of water to learn more about the patterns and amounts of farm water use. In South Carolina, surface water assessments, model calibration and development, and stakeholder engagement processes occurred through 2017, with stakeholder meetings held in each of the state’s eight river basins. Three surface water models were also released to the public in 2018 with additional surface and groundwater models expected in 2019.

- Connecting river flows to clean water – In 2017, for the first time, South Carolina put a waterway (the Upper Saluda River) on its list of impaired waters (303(d) list) due to hydrologic impairment, providing impetus to correct the problem.

And there were a few set-backs:

- Tennessee – Historically, Tennessee has protected river flows through both water withdrawal permitting and narrative criteria for flow as part of state water quality standards. However, TDEC has proposed a series of rule changes that, if successfully promulgated, could result in weakening of these protections for river flows. Similarly, until 2016, Tennessee had some of the best requirements for onsite retention of stormwater in the Southeast including performance standards requiring that the first inch of rainfall be 100% managed on-site through runoff reduction or harvesting techniques. A revised draft permit that weakened these requirements was challenged by homebuilder and environmental groups. Under the terms of the settlement, the state will require stormwater control measures to be designed, at a minimum, to capture 80% of total suspended solids and permittees are required to establish and maintain permanent water quality riparian buffers.

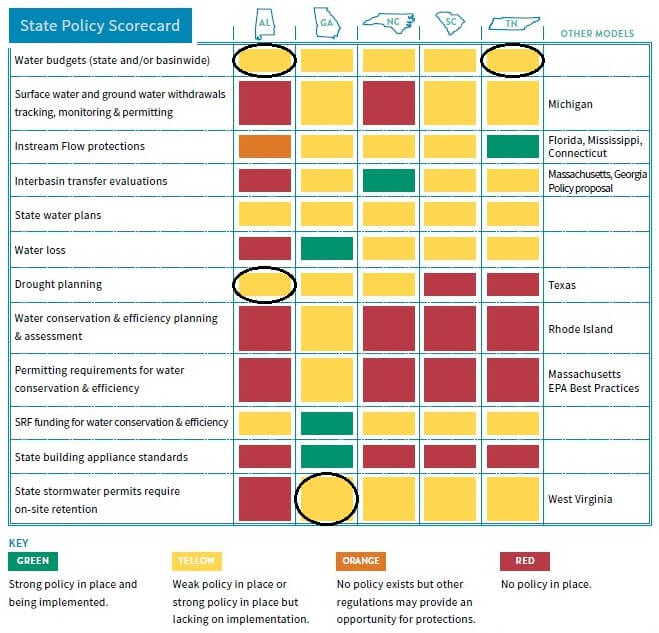

To summarize the status of the policies reviewed in the report, we developed a scorecard that illustrates how each state rates in each of the policy areas and highlights other states where model policies have been implemented. The circles indicate where a state’s status changed between 2016 and 2019.

-

[…] Read more about our current Southeast work and hear from Matt Rota, a former CWA “trainee” in Louisiana who continues to share his CWA knowledge with others. […]

Leave a Comment

One thought on the presumed “positive” policy of detaining the 1st inch of stormwater onsite (Georgia write up) is that it may encourage the conversion of wetlands to retention ponds thus eliminating some natural detention and treatment. These ponds are certainly not a panacea and have their own problems such as receiving high nutrient loads and chemicals from residential lawns and often having nasty algal blooms or attracting nuisance geese.

Hi Steve – Thanks for reading the blog post and for your thoughts. Agreed – protecting natural infrastructure is always the preferred option. It seems like Georgia’s permit favors “retention” instead of detention – and the on-site capture requirement combines with a preference for green infrastructure which hopefully allows for practices like protection and restoration of wetlands. Of course, successful implementation of the rule will be also be essential to ensuring the rule change is beneficial for river flows. Are you aware of other permits or rules that have been successful that we might highlight?